Prevention is Better than Cure: The High Cost of Public Service Workers Psychosocial Injuries

The connection between public sector workers and psychosocial injuries is a serious issue. These injuries are becoming increasingly common among public sector workers, particularly those in community and community-facing roles.

In Brief

The connection between public sector workers and psychosocial injuries is a serious issue. These injuries are becoming increasingly common among public sector workers, particularly those in community and community-facing roles.

In this article, we explore why such workers are at risk, the challenges they face in their roles, the effects of psychosocial injuries on the public sector, and strategies for assessing these risks.

The Rise of Psychosocial Injury in the Public Sector

Public sector workers are at the forefront of community engagement and response, particularly at times of crisis. Our Commonwealth, state and local public servants meets members of our communities on their worst day and work to provide support, bad news or available options in a way that is compassionate and reflective of wider policy.

Public servants are entitled to psychological safety, and have been since before harmonised OHS laws were implemented.

Recent changes to laws across Australia, including the implementation of specific guidelines and codes of practice for psychological safety have brought into focus the risk of psychological injury, and the importance of understanding risks as applicable to different workforces, workplaces and types of work while applying a creative mindset to the assessment and management of risk.

The Law

Under state and commonwealth legislation a 'psychosocial hazard' is as a hazard that:

-

Arises from or relates to the design or management of work, a work environment, plant at a workplace, or workplace interactions or behaviours; and

-

When unaddressed, psychosocial hazards can lead to psychosocial injury (i.e., PTSD, depression, anxiety).

In the event any member of staff suffers a psychological injury, claims may be brought for injury arising from work. Such injuries may also be investigated by workplace health and safety regulators.

Psychological injuries are expensive. Staff generally take longer to recover from psychological injury than from many physical injuries. Psychological may prevent a person from returning to their pre-injury position. Consequently, psychological injuries are not only expensive but operationally challenging, which can place strain on other staff, leading to further risk.

Having regard to the clear obligation to assess and manage this risk and the cost of getting it wrong, prevention is better must be an better option than cure.

Assessing the Risk of Psychosocial Harm

To assess risk an employer needs good data.

Data related to psychosocial risk can take several forms including absenteeism, presenteeism, retention and turnover, complaints and grievance (or a lack of complaints), exit interviews and reports, and injury and compensation claims.

Workplace surveys also provide a useful data for setting a baseline around morale, identifying risk, defining responses to identified issues and tracking improvements with the goal of improving employee safety and the work environment and to meet legislative obligations.

Whether these hazards are physical or psychosocial in nature, they need to be eliminated or managed to ensure that government supports the health and wellbeing of their employers, as far as reasonably practicable.

Identifying and implementing support can be difficult where the work of public servants is so varied. However, where much of the work of the public service involves:

-

significant emotional demands;

-

exposure to stress and possibly traumatic events; or

-

ongoing and prolonged management of conflict between staff, clients, stakeholders and others,

consideration needs to be given to available supports and controls, including:

-

what risks can be eliminated or managed and how. Is it possible to exit or limit contact with staff, clients or others who create unreasonably increase emotional demands, cause stress or prolonged and unmanaged conflict?

-

the design of workplaces, workspaces and leave. Do public servants have a 'safe space' to retreat to, down time and the ability to disconnect; and

-

the support available including EAP, proactive training and resilience initiatives, access to leave to prevent decompensation and assessment of emerging mental health symptoms.

Supports and controls should be reviewed regularly and as demands change, so as to keep people safe, as far as reasonably possible, but also because it is the law.

Fortunately there is specific guidance to public service employers about managing specific psychological risks. Specifically this guidance provides that psychological risk can be better managed by:

-

Better workplace design;

-

Increased consultation around work management;

-

Improved job design, reward and recognition, role clarity and job control;

-

Better direct support, practical and emotional assistance from managers and colleagues;

-

Focus on setting standards and support around workplace interactions, behaviours, resilience and emotional intelligence;

-

Improved consultation around change management, restructures and reviews of operations, including amendment to industrial provisions;

-

Recognising the impact of bullying, aggression, conflict, violence and harassment as well as the impact of 'out of hours' matters like family and domestic violence;

-

Understanding the risk of remote and isolated work, trauma in the workplace or in the nature of work.

Collectively these actions might be seen as opportunities to improve psychological safety and improve statutory compliance. Individually they provide useful action items and opportunities for consultation to address safety. For example:

| Opportunities to improve psychological safety | Possible consultation and responses |

| Improved job design | Would greater access to online services reduce the risk of staff being abused or subject to violence? |

| Better workplace design | Does the workplace ensure the physical safety of staff from assault or violence? Do they have an opportunity to have a break from the demands of work? |

| Industrial provisions | Can they be amended to change the span of working hours to allow for greater flexibility around burnout, anxiety or compassion fatigue? |

| Understanding the nature of the work | How might a team reconsider work activity to improve job control? |

| Understanding the risk of isolated work | Ensuring regular in-person check-ins, asking people to come to the workplace if they are experiencing isolation, and conducting mental health assessments as part of working from-home checks |

Using the opportunities to improve psychological safety as a guide to engagement with staff is an important way for Government at all levels to consult and directly address psychological risk visibly and interactively with staff. The responses do not need to be expensive or give rise to significant unbudgeted spend, though at times such a response will be needed. The benefits of direct engagement about psychological risk by involving teams in the design of work might assist to demonstrate an immediate commitment to improvement.

Psychosocial Management Checklist

To ensure departments and agencies manage psychologically safety, risks need to be assessed, controls identified and implemented and reviewed for effectiveness to understand how the above opportunities to improve psychological safety are being addressed or might be addressed in your department and workplace.

Such reviews can deliver significant benefits to departments. For example, mental health claims are the most prevalent type of claim in government across Australia. In August 2024 it was estimated that preventing 19 psychological injuries in the Commonwealth public service alone could save close to $20 million in costs. Where psychological injuries take longer to resolve and generally cost more than physical injuries to support, prevention is better (and cheaper and more people-focused) than the cure.

In addition to improving staff safety, there are good personal and financial reasons to ensure that safety is an action item in all interactions.

Recent reforms, charges and cases

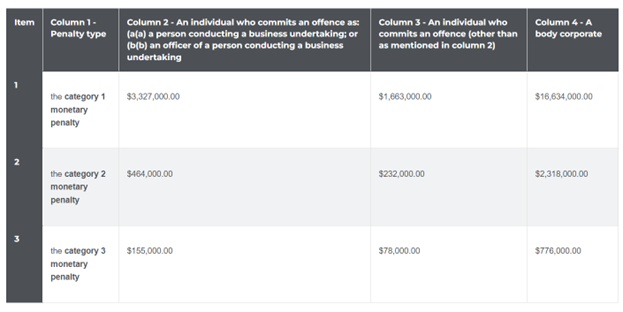

From 1 July 2024 penalties for breach of the WHS Act have increased. In addition, new criminal responsibility provisions also promote accountability for bodies corporate and government for breaches of work health and safety duties.

In New South Wales the regulator plans to increase inspections of psychological risk by 20% this financial year, focusing on ensuring workplaces and government agencies adopt a proactive and preventative approach to psychological health and safety. Coupled with the Broderick review in Queensland of Queensland Health and Ambulance services, requiring agencies and healthcare providers to prevent harassment in the workplace, government at all levels must be prepared for increased scrutiny of workplace responses to psychological risk.

In view of these changes and challenges the conduct of officers, employees and agents and authorised persons, and/or the board of directors for a body corporate, can be found personally responsible for breaches of workplace health and safety duties:

Governments are not beyond prosecution.

This month the WA State Department of Justice is the first duty holder to be charged with failing to attempt to control psychosocial hazards. They face a fine of more than $3 million, in addition to a $900,000 safety fine issued in 2022, after a female prison officer was caused serious psychological harm as a result of the Department failing to implement procedures address inappropriate workplace behaviour including bullying, sexual harassment and victimisation.

The Department of Defence was similarly charged with category 2 and 3 breaches in May 2024 for allegedly exposing a ADF member in Queensland to the risk of death, or injury (including suicide) by failing to adequately control mental health stressors associated with isolation from their chain of command. Where the risk might have been managed by regular in person check-ins and conducting mental health, the risk might have been eliminated or reasonably managed.

Where some of the risks for government employees are perceived to have been unmanaged, specific legislation is being considered by the Commonwealth Parliament to address the risk to workers in the Commonwealth Parliament. If the Parliamentary Workplace Support Service Amendment (Independent Parliamentary Standards Commission) Bill 2024, (which passed on 13 September 2024) Parliamentarians and their staff will face training orders and personal financial penalties for bullying and harassment. Recent allegations regarding the Deputy Prime Minister's office may further highlight the issue.

Similar legislation is being considered in other jurisdictions to address safety in government workplaces to support existing state and federal legislation which addresses adverse action, bullying and harassment in the workplace.

Further, the commonwealth government has committed $1.5 million to conduct a comprehensive independent legal review of the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988. Reform can be expected at the state and government level to address psychological risk in workplaces.

The consideration of risk should take into account the cohort of a workplace and any specific risk factors applicable to them.

For example, the state government in Queensland has introduced different types of leave to address the risks associated with reproductive health. Where approximately 60% of public servants across Australia are women, it is recognised that reproductive issues can impact on a woman's mental health and wellbeing, as well as positive engagement in the workforce. The question of reproductive leave has been considered by a Commonwealth senate inquiry. Last year that inquiry recommended reproductive leave be considered by the Commonwealth government as a workplace flexibility and risk management response as well as a means of keeping women, particularly older women in the workplace longer.

Similarly suggested amendments to the Commonwealth Criminal Code, to treat assault of frontline workers the same as the assault of judicial or law enforcement officers, have been proposed in response to the stabbing of a Commonwealth government front-line worker who was stabbed while performing a customer service role. The proposed amendment recognises the importance of government agencies and their service culture, while confirming their right to safety at work, in response to 500 workers saying that they do not feel safe or that their safety is prioritised.

Takeaways

The human cost of psychological injury in the public sector is significant. Consequently wholistic responses are needed by departments and agencies. Responses should focus on behaviours, psychological support (including things like behaviour therapy), early intervention to respond to mild depression and anxiety as well as continued review of opportunities to improve physical and psychological safety.

Government must also consider policy and legislative responses to workplace risks applicable to different cohorts.

Employers must get the basics right like work design, ensuring reasonable job demands and building manager capacity. Training around expectations around bullying and harassment are also important to ensure that public sector employees can be safe at work.

As an immediate action item, government departments and agencies at the local, state and commonwealth level can look to the

While it can be tempting to focus on the challenge and the failings, the efforts taken by government at all levels to manage psychological risk should be recognised. Naturally, this is not a process that happens overnight.

Contact Colin Biggers & Paisley today for expert advice, training and support.