High Court dismisses Pafburn appeal - but this does not mark the end of apportionment in construction cases

By Jonathan Newby, Laura Reisz, John Georgas and Sean Turner

In a 4:3 split decision, the High Court has dismissed the appeal of Pafburn (The Owners – Strata Plan No 84674 v Pafburn Pty Ltd [2023] NSWCA 301), with the majority finding that those who delegate or entrust work to others cannot seek to exclude or limit their liability via the apportionment regime.

In brief

In a 4:3 split decision, the High Court has dismissed the appeal of Pafburn (The Owners – Strata Plan No 84674 v Pafburn Pty Ltd [2023] NSWCA 301), with the majority finding that those who delegate or entrust work to others cannot seek to exclude or limit their liability via the apportionment regime, i.e. the proportionate liability defence is not available for "upstream parties" who delegate work to others.

As to "downstream parties" who do not delegate work, the majority did not address the question of what is effective control over "construction work", and as such the question of whether a proportionate liability defence remains available for these parties has not been clarified.

In other words, the majority did not completely dismiss the potential application of Part 4 of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (CLA) to claims for breach of the statutory duty of care under the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (NSW) (DBP Act). There remains a possibility that certain professionals, such as certifiers, project managers, land surveyors, and most engineers who seldom delegate work to others can continue to apportion liability with concurrent wrongdoers.

Before we go into further detail, here are the facts.

Facts

-

The subject property is a multi-story residential building in North Sydney, constructed between 2008 and 2010 by Pafburn as the builder. Madarina was the developer.

-

The Owners Corporation for the property commenced proceedings against Pafburn and Madarina on 1 December 2020, 5 days within the 10 year "long stop" limitation period, for alleged breaches of the statutory duty of care under the DBP Act. Specifically, the Owners Corporation alleges that Pafburn constructed the building defectively and that Madarina "supervised, coordinated, project managed and substantively controlled…the building work carried out by Pafburn".

-

Both defendants plead proportionate liability and name nine concurrent wrongdoers, including the architect, the installer of aluminium composite panels (ACPs), the manufacturer of those panels, the certifier, and other sub-contractors.

Primary decision

-

On 16 February 2023, the Owners Corporation brought an application to strike out the defendants' proportionate liability defences on the basis that:

a. the duty of care under the DBP Act is non-delegable (which was uncontroversial noting s 39 of the DBP Act is explicit in that a person who owes a duty of care under s 37 of the DBP Act is not entitled to delegate it); and

b. the combined effect of s 39 of the DBP Act and s 5Q and 39(a) of the CLA prevented the defendants from relying on the proportionate liability provisions where the statutory duty was non-delegable. -

The defendants succeeded in opposing the application and their apportionment defences remained intact.

- For reference later on in this article, s 5Q of the CLA says that a non-delegable duty falls outside s 5A, which is what introduces proportionate liability to claims involving a failure to take reasonable care. A key feature of s 5Q is that the test of liability it introduces is quite specific - it is to:

"…ensure that reasonable care is taken by a person in the carrying out of any work or task delegated or otherwise entrusted to the [negligent] person by the defendant…"

Court of Appeal

-

The Owners Corporation successfully appealed the first instance decision, with the Court of Appeal finding that:

a. because the duty of care under s 37 of the DBP Act was non-delegable, the CLA treats breach of it as a form of vicarious liability by operation of s 5Q of the CLA, meaning it cannot be reduced by the liability of others; and

b. more broadly, that s 39 of the DBP Act (which provides that the statutory duty of care may not be delegated) is sufficient to exclude Part 4 of the CLA in its entirety (i.e. apportionment). -

In effect, when a defendant breaches its duty of care under the DBP Act, it will be held wholly liable for the plaintiff's loss. While the defendant may still cross-claim against concurrent wrongdoers, this would be solely a matter of recovery and would not diminish the defendant's liability to the plaintiff.

-

We know that many defendants have filed cross-claims after the Court of Appeal handed down its decision on 13 December 2023. However, the decision sparked considerable debate because it became unclear whether it applied to everyone who performed construction work, or just those who sub-contracted or entrusted their work to others. For example, the manufacturer of the ACPs, who was not contracted by either Pafburn or Madrina to manufacture the panels; would they still be found 100% liable for the (allegedly) defective panels? Or the certifier, who was engaged to provide services rather than carry out construction work on behalf of Pafburn or Madrina.

High Court

-

In dismissing the appeal, the majority of the High Court (comprising Gageler CJ, Gleeson J, Jagot J, and Beech-Jones J) affirmed that apportionment is not available to those who delegate or entrust "construction work" to others - they will be held 100% liable for any defects arising from those works.

-

In this particular case:

a. Madarina, as the developer, was allegedly responsible for supervising, coordinating, project managing or otherwise having substantive control over the construction of the building as a whole; and

b. Pafburn, as the builder, was responsible for constructing the building as a whole. -

Madarina delegated or entrusted the construction of the entire building to Pafburn and in doing so, "supervised" the whole of that work. If there are defects in the building, Madrina will be vicariously liable for them.

-

Pafburn was responsible for the construction of the entire building and in doing so, sub-contract many kinds of construction work to others. However, Pafburn still retained a duty of care over the works and so it too will be found 100% liable for any defects.

-

But what about certifiers, project managers, land surveyors, and most engineers who seldom delegate to others? Although the majority did not express a view on these professionals, it remains open for them to plead apportionment in circumstances where the majority concluded:

"if [a plaintiff] establishes such alleged breaches but fails to establish that those breaches caused the whole of the claimed economic loss, [the defendant] will be found liable only to the extent that their breaches caused the loss." -

If professionals do not delegate or entrust work to others, they will be found liable only to the extent they caused the loss. Whether that means they will be found wholly liable for the defects they contributed to, or just partially liable is still up for debate.

-

There is also a possibility that apportionment is available against certifiers, noting the High Court assumed (based on Pafburn and Madarina's List Responses) that the principal certifying authority exercised "substantive control" over the carrying out of the construction work and therefore "carried out construction work" within the meaning of d 37 of the DBP Act. On that assumption, Pafburn or Madarina would be vicariously liable for the failures of the certifier. However, whether certifiers are captured by the DBP Act is still up for debate, with Chief Justice Hammerschlag recently commenting:

"This is undoubtedly an important issue, particularly to the building and construction industry. It is, in my opinion, one manifestly worthy of appellate consideration, perhaps even by the High Court." (The Owners Corporation SP 90832 v Dyldam Developments Pty Ltd [2024] NSWSC 1519, [28].) -

The minority in Pafburn also said that "is not self-evident that a certifier or the local council, in performing their duties, is 'a person who carries out construction work'."

The Minority view

-

The minority (comprising Gordon J, Edelman J, and Steward J) found that the proportionate liability scheme under Part 4 of the CLA does apply to a claim for damages for breach of s 37 of the DBP Act.

-

The phrase "a person who carries out construction work" in s 37 of the DBP Act does not extend beyond the actual carrying out of construction work by the person or their agent. It does not include strict liability for work carried out by sub-contractors. The fact that s 39 prohibits a person from delegating the duty under Part 4, does not transform the duty into a traditional common law non-delegable duty to ensure that reasonable care is taken by sub-contractors. In other words, it does not extend the duty to the work of independent contractors.

-

Section 5Q of the CLA does not apply to liability for breach of the duty of care under s 37 of the DBP Act. That is because s 37 is not a duty to ensure reasonable care is taken - it is a personal duty to take reasonable care to avoid economic loss caused by defects.

-

In the case of multiple wrongdoers causing the same damage or loss jointly or independently, s 39(c) does not apply because the DBP Act does not impose several liability in respect of what would otherwise be an apportionable claim. That would put the wrongdoers in the position of concurrent wrongdoers at common law and thus jointly and severally liable for the loss claimed.

Take-aways and implications

-

In circumstances where there has been a split decision, it is important to identify where the majority and the minority disagreed. Those points are as follows:

a. the application of s 5Q of the CLA to a claim for damages for breach of s 37 of the DBP Act (majority says yes, minority says no); and

b. the content of the duty of care, specifically, whether it extends to construction work performed by independent contractors. -

The majority did not, however, state Part 4 of the CLA does not apply at all. Rather, the majority say that these two factors, taken together, mean that the appellants could never have excluded or limited their liability via the apportionment regime as both of them (on the owners corporation's case) engaged in "construction work" for the whole of the building, therefore making them vicariously liable for the actions of whomever it was downstream of them that failed to take reasonable care. The result of this makes the question of whether Part 4 of the CLA applies to claims for breach of s 37 of the DBP Act unnecessary to decide in the context of an appeal brought by the two most upstream parties.

-

Whether apportionment is available to construction professionals in some limited circumstances is still up for debate and the High Court certainly has not closed the door on the possibility. It will take another case to test the point, or legislative intervention.

-

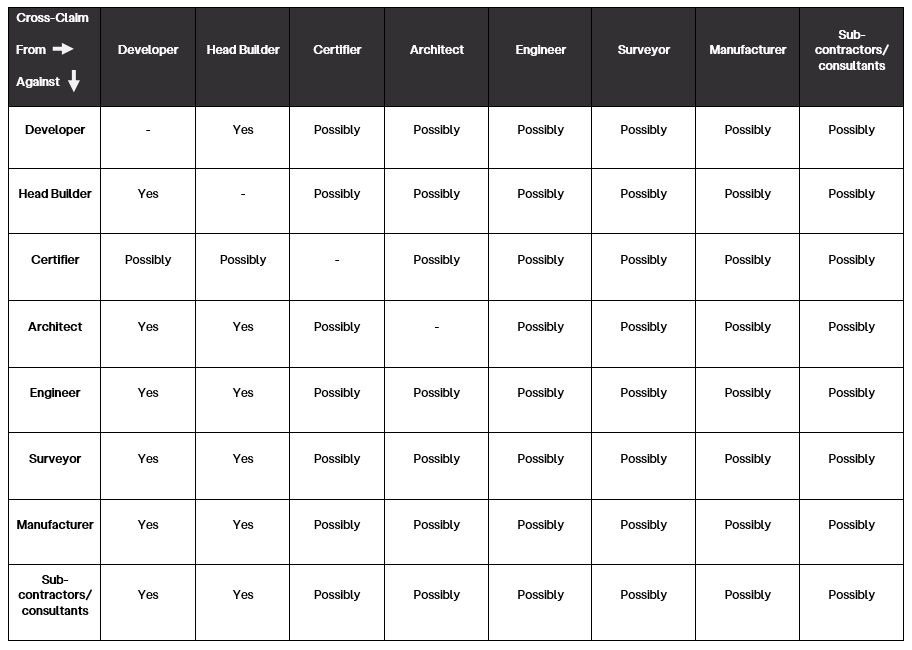

Based on the current state of the law, here are some cross-claims requirements:

-

The number of "possible" scenarios reflects the lingering uncertainty in the law and the reality that the need to file cross-claims will depend on the individual facts of each case. There may be instances where an engineer needs to file cross-claims against its sub-consultants, if for example they delegate aspects of their design to draftspersons.

-

What is clear from the decision is that upstream parties, such as developers and head contractors will now face an increased exposure for defects, as they can no longer apportion liability downstream. They may still cross-claim against their sub-contractors and consultants, which means the landscape for professionals and their insurers remains (in effect) the same.